I said goodbye to Timisoara and Romania at noon today. Nearly every town and village has some kind of sign saying ‘Drum Bun’, which literally means Good Road i.e Safe Journey. I had stayed in Timisoara both because it was where I stayed when I first arrived in Romania and because, 21 years later, it became Romania’s “first free city”, the incubator of the 1989 Revolution. I did not remember that the initial spark was a reaction against the state’s attempt to force the eviction of a dissident priest in the Hungarian Reformed Church, László Tőkés. The demonstration of some 200 outside the church house in S. Maria Square was what grew overnight into a bigger demonstration in the main square in front of the Opera House, now named Victory Square.

From the start, the crowds had chanted “Down with Ceasescu” and, as they grew in number, undaunted by the forces of law and order, Ceasescu panicked and ordered the troops to open fire. The bodies of those killed then were taken from the local hospital, and both they and the incriminating documents were burned. But the crowds said: “We won’t go home. The dead won’t allow us to go home”. Over the seven days that this movement took – spreading to other cities – to depose him, 110 people of all ages were shot dead in Timisoara. Initially, Ceasescu bussed in faithful peasant followers from around the region of Oltenia to oppose the demonstrators, calling them ‘hooligans’ and ‘fascists’. One statement termed them ‘Hungarian hooligans’, underlining the faultlines which were still exploitable in Romanian society. Yet the evidence is that people from all religious traditions and social backgrounds joined in these events.

I learned a lot more from one demonstrator, then a 44-year old vet, Dr Traian Orban, who was shot in the thigh and eventually had to go to Vienna for surgery. He said the Romanian doctors wanted to amputate his leg, just as the regime’s violence amputated others’ arms, legs and children.

Since his recovery, Dr Orban has run the Permanent Exhibition of the 1989 Revolution museum in Timisoara, dedicated to the memory of what he calls both a political and a spiritual revolution, combining people of all faiths. They have a graveyard for the dead in the north of the city – not dissimilar to military graveyards on First World War battlefields – and have commissioned memorial sculptures at a dozen sights around the city where people died. These are the maquettes, each reflecting different aspects of the sacrifices made.

The walls are covered with everything from photographs and world news coverage of December 1989 to the children’s painted depicted memories and a collection of flags waved in the crowd, with Communist party logos cut out of some of them.

The museum has much in common with the Bloody Sunday museum in Derry, also an unfunded commitment to the act of memory, lest people forget those who lost their lives peacefully opposing forces of oppression. Dr Orban is keen to make international connections and collaborate in research work around the museum’s focus, agreeing that the Romanian state invests far too little in cultural history. He says many in power regret his work, wishing the uncomfortable past to be forgotten. It is all too appropriate that they have a section of the Berlin Wall outside the museum, a visceral connection with a symbol whose breaching in November 1989 was undoubtedly encouragement to the brave people of Timisoara six weeks later.

Memory is a powerful, if malleable, human trait, which needs nurturing. It sustains negative, as well as positive, feelings. When filming in Beograd – which I passed through again today – in 1993, our Serbian commentator spoke of hearing people speak excitedly of something which sounded as if it happened yesterday, only to realise that it had actually happened a hundred years ago. It was that kind of visceral tribal memory which had risen, no longer regulated by Tito’s Yugoslav federalism, to engorge people’s minds, leading to blood running instead of reason. So carefully curated factual memories, however laden with tragedy and emotion, are vital to preserve perspective and – optimistically – guard against repeat performances.

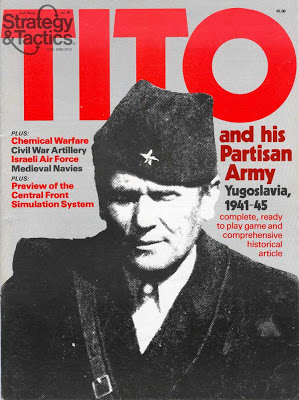

Crossing from the scene of one recent traumatic history to that of another gave me something of an historical overload. I am staying in Uzice, the first free republic to be declared by Marshal Tito’s Partisans in 1941. The Germans recaptured it after two months, through Operation Uzice, with the Serb Chetniks switching from supporting the Partisans to attacking them, albeit unsuccessfully. Uzice was eventually lost because Germany saw it as crucial to suppress the Communist revolt, and threw everything at it, with the help of Serb collaborationists. They declared Serbia a war zone, assuming all Serbs hostile and were instructed to kill 50-100 Serbs for every German killed. Villages were torched and several thousand Serbs executed. Elsewhere, around 100,000 Serbs were perishing at the hands of the extreme Croat nationalists and Nazi sympathisers, the Usatasi, in their infamous Jasenovac concentration camp. This is another community with history hanging heavily on its shoulders. The local military museum was an arms factory, marked now by this model tank.

On the riverside at evening, it is hard to imagine the wars that have raged around here, but these and the hurt last long in their minds. And the landscape carries many living memories of the mixed cards fate has dealt. Whereas the Romanian land is disfigured by those half-completed houses awaiting their migrant owners’ return, the Serbian land is also replete with half-finished buildings and businesses, aborted by the outbreak of the Balkan war, and now never to be finished. While Romania’s cup is half full, Serbia’s is half empty. Yet Yugoslavia was the mixed economy success, and many of its fragmented parts have adapted well to capitalism. Romania, however, is full of redundant and rotting industrial plant, which had been kept inefficiently going under the communist command economy, but which collapsed quickly under market rules. The Redauti Beer and Spirit Factory was a case in point, reputedly Romania’s oldest brewery, it had been going for 200 years before it collapsed in the 1990s.

All this dereliction is an unhealthy reminder of the past, whereas people deserve their history better presented and told than many of the Romanian museums I have visited. When people grab hold of their own history – like the wounded veteran of the ’89 Revolution or the nuns of Agapia – the result is charged with meaning. Both Romania and Serbia need to lay their troubles to rest through a more coherent and comprehensive cataloguing of memory and memorabilia. Virginia Woolf wrote:

“I can only note that the past is beautiful because one never realises an emotion at the time. It expands later, and thus we don’t have complete emotions about the present, only about the past.”