This extraordinary edifice in the Antwerp docks stands for the uncomfortable accommodation of old and new you often find in Europe. Looking like a giant inter-galactic space bug trying to mate with a 19th century asylum, it seems to come from the same impulse which drives schoolboys to put a moustache on the Mona Lisa. Its designer also probably didn’t consider the problems it presents window cleaners, two teams of which you can see here on extended cherry-pickers. Gruelling work if you can get it, though I didn’t ask them if they were EU migrants depriving plucky Belgians of the opportunity.

This extraordinary edifice in the Antwerp docks stands for the uncomfortable accommodation of old and new you often find in Europe. Looking like a giant inter-galactic space bug trying to mate with a 19th century asylum, it seems to come from the same impulse which drives schoolboys to put a moustache on the Mona Lisa. Its designer also probably didn’t consider the problems it presents window cleaners, two teams of which you can see here on extended cherry-pickers. Gruelling work if you can get it, though I didn’t ask them if they were EU migrants depriving plucky Belgians of the opportunity.

It is also apparent that the EU does not breed uniformity. Whilst most of Europe now accepts motorway speed limits of 120 or 130 kph (74-80 mph), Germany is famous for having no upper speed limit, unless specifically delimited on certain stretches. So the European habit of sitting on your tail, demanding you move over out of their way, reaches new heights here, with cars bearing down on you at up to 200mph. Most of them are upper range SUVs, which look as if designed to invade Poland, and today well over 80 per cent of them are black, not that that is anything to get shirty about. Nonetheless, whizzing through Belgium, Holland and Germany, barely aware of the control-free borders, reaffirms the value of the central EU tenet of freedom of movement. Germans speak to me of the pleasure of driving to Spain or the south of France without let or hindrance. It is not, as the myopic little Brits think, merely a chance to come to Britain to steal our jobs and rip off our health service. Most Europeans have better jobs and services, but the arrogant insular mentality sees all arrivals as invasion, like the maiden aunt imagining every male to be a prospective rapist. Hence the provocative, paranoid propaganda of the leave campaign warning of a flood of sexual attackers.

It is also apparent that the EU does not breed uniformity. Whilst most of Europe now accepts motorway speed limits of 120 or 130 kph (74-80 mph), Germany is famous for having no upper speed limit, unless specifically delimited on certain stretches. So the European habit of sitting on your tail, demanding you move over out of their way, reaches new heights here, with cars bearing down on you at up to 200mph. Most of them are upper range SUVs, which look as if designed to invade Poland, and today well over 80 per cent of them are black, not that that is anything to get shirty about. Nonetheless, whizzing through Belgium, Holland and Germany, barely aware of the control-free borders, reaffirms the value of the central EU tenet of freedom of movement. Germans speak to me of the pleasure of driving to Spain or the south of France without let or hindrance. It is not, as the myopic little Brits think, merely a chance to come to Britain to steal our jobs and rip off our health service. Most Europeans have better jobs and services, but the arrogant insular mentality sees all arrivals as invasion, like the maiden aunt imagining every male to be a prospective rapist. Hence the provocative, paranoid propaganda of the leave campaign warning of a flood of sexual attackers.

Having travelled widely since a teenager, I too appreciate the freedom of movement, and recognise what a threat secession will be to people in Ireland no longer free to move from North to South. More importantly, what travel tells me is that people everywhere are essentially the same, mostly honest, hard-working individuals looking out for their families. They may speak a different language, eat different food, sometimes have funny clothes and customs, but we share much more than we differ. The problem with the media, which I know from first hand, is that news requires sensation and television more generally requires exotic novelty. What no editor or commissioner wants to here is that Johnny Foreigner is just like us. The further and more costly your travel expenses are, the more the pressure is on to underline the difference, paint up the contrasts. The newfound taste for Scandi-Noir and other foreign television dramas at least represents a desire for recognisable shared normality, but their audiences are not those lining up to vote Leave. That constituency has been fuelled with a constant fear of ‘the other’ by the red-tops they read, given expression and fellow feeling when travelling abroad to support their national footballers.

I stayed in a self-described rock and roll pub hotel near Hamburg’s Fischmarkt, so that I could walk to this famous market’s early morning opening on Sunday, and found myself in a wonderfully heterogenous bo-ho area, with every type from hippies living in caravans on the street, to young families and African drug sellers on the corner. The sex district of the Reeperbahn is just around the corner, but the atmosphere was friendly and people seemed to get along well. I spent part of my evening chatting to two young Germans up from Munster for a stag weekend. Not only would their decision to leave the rest of the group to sample the vegan restaurant next door to my hotel be improbable on a British stag party but, despite dead-end jobs, they were also both clued up and keen to talk about Brexit. They cannot understand why a nation would want to commit economic suicide, and this was a tax office clerk and a heavily tattooed warehouse logistics supervisor talking. They were no more enamoured of politics & politicians than their British equivalents, and every bit as interested in beer and cigarettes, but they had a refreshingly educated take on things.

I stayed in a self-described rock and roll pub hotel near Hamburg’s Fischmarkt, so that I could walk to this famous market’s early morning opening on Sunday, and found myself in a wonderfully heterogenous bo-ho area, with every type from hippies living in caravans on the street, to young families and African drug sellers on the corner. The sex district of the Reeperbahn is just around the corner, but the atmosphere was friendly and people seemed to get along well. I spent part of my evening chatting to two young Germans up from Munster for a stag weekend. Not only would their decision to leave the rest of the group to sample the vegan restaurant next door to my hotel be improbable on a British stag party but, despite dead-end jobs, they were also both clued up and keen to talk about Brexit. They cannot understand why a nation would want to commit economic suicide, and this was a tax office clerk and a heavily tattooed warehouse logistics supervisor talking. They were no more enamoured of politics & politicians than their British equivalents, and every bit as interested in beer and cigarettes, but they had a refreshingly educated take on things.

Earlier I had been on a tour of the Hamburg Rathaus, one of the most rococo town halls in existence. As a city state – Germany is a federation of 16 states – Hamburg has its own parliament and senate, housed in this extraordinary palace since 1897. Long before that, Hamburg was leading member of the Hanseatic League, a forerunner of the EU as the trading association which dominated north Europe from the 12th to the 16th centuries. The young guide enthusing about this tradition made me wonder whether having such serious local government for a locality of just 1.7 million people might be one reason why Germans are better connected to their democratic system than Brits are. Another is that their 20th century history has enforced on them a painful reckoning with the past and the determination to never go there again. (The Rathaus also had a harrowing exhibition about the Nazi policy of exterminating the mentally ill.) Whereas Little Britain seems determined to be backward-looking, with both sides claiming Churchill for their cause.

Earlier I had been on a tour of the Hamburg Rathaus, one of the most rococo town halls in existence. As a city state – Germany is a federation of 16 states – Hamburg has its own parliament and senate, housed in this extraordinary palace since 1897. Long before that, Hamburg was leading member of the Hanseatic League, a forerunner of the EU as the trading association which dominated north Europe from the 12th to the 16th centuries. The young guide enthusing about this tradition made me wonder whether having such serious local government for a locality of just 1.7 million people might be one reason why Germans are better connected to their democratic system than Brits are. Another is that their 20th century history has enforced on them a painful reckoning with the past and the determination to never go there again. (The Rathaus also had a harrowing exhibition about the Nazi policy of exterminating the mentally ill.) Whereas Little Britain seems determined to be backward-looking, with both sides claiming Churchill for their cause.

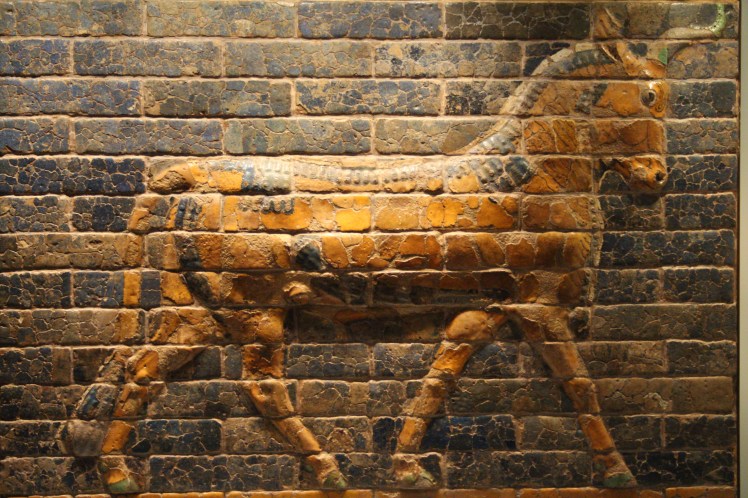

As the Oxford historian Peter Frankopan says, in his The Silk Roads, we have been fed a lazy, narrow Western view of world history, which causes a distorting, self-regarding myopia. While our ancestors were still whittling flint tools 2,500 years ago, the Persian Empire stretched from the Aegean to the Himalayas, also having conquered Egypt. They built great gilded palaces and roads which enabled them to speed across their empire, but they didn’t essay the crude 21st century UK-US jingoistic attempt to impose their own traditions. Herodotus writes: “The Persians are greatly inclined to adopt foreign customs” including changing their mode of dress where it appealed, and Frankopan says “their tolerance of minorities was legendary”. Strangely, the denizens of Persepolis didn’t vote to get out of empire because there were too many foreigners about affecting the way they did things. That’s where the above gent is from, currently appearing in an excellent display on The Ancient Mediterranean at the NY Carlsberg Glyptotek Museum in Copenhagen, along with this bull wall commissioned by King Nebuchednezzar of Babylon.

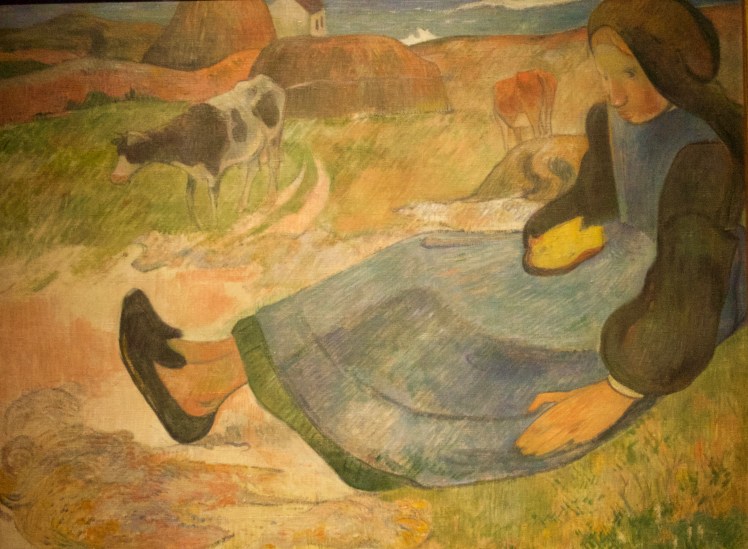

The Glyptotek also has an astonishing number of fine French paintings and sculpture, and is currently running a special exhibition of their unrivalled collection of Gaugin works, Gaugin’s Worlds. (His wife, Mette, was Danish and he lived here for a while.) Here again, I encounter a restless mind who craved new, different experience to refresh and inform his artistic vision, travelling to Guadeloupe and Tahiti long before long-haul travel was made easy. He revelled in the different concepts of beauty he found, in artefacts and people, and his painting, pots and carvings all rejoice in that liberation from the European aesthetic.

On return, Gaugin painted the people of Brittany as exotically different, his eye sharpened by his travels. From the 18th century artists and academics, romantics and revellers have travelled to broaden their mind and enjoy the wealth of other cultures. I know that leaving the EU won’t stop that, but it will make it harder to afford, and Europe will be like a lover spurned, less likely to be so open.

Copenhagen today: