I have been silent for months as the Brexit tragedy has unfolded, the whole fiasco being driven by self-seeking cynics who have a very contemporary aversion to the truth, which rendered intelligent discourse increasingly unsustainable. The mirthless joke is that those same charlatans are now in charge of the country as it faces its darkest hour since World War II; and the mendacious buffoon in the eye of the storm is he who always fancied himself as a renascent Churchill, although frighteningly lacking in the vision and oratory of his hero. The ultimate irony: the virus has achieved their ultimate goal of cutting us off from Europe and ‘taking back control’ far more effectively than their half-baked plans. Those plans and their undoubtedly negative economic effects are now buried beneath the viral tsunami, probably making it impossible ever to identify the actual cost of Brexit.

Confined to quarters, I am bound to consider what else this isolation portends, for us as individuals and for the wider world. The postponement of the Olympics for a year is arguably the most global of all the multiple impacts that the corona pandemic has caused. It is only eighteen months since we visited Olympia for the first time, having to negotiate our way past coaches disgorging hundreds of tourists from around the world. This was the site where the Olympics was initiated sometime in the eighth century BC (historians disagree as to whether it was 776 , 765 or another year), thus prompting an Olympic truce among the warring Hellenic states every four years. So the Olympics was a kind of early infant European Union, continued after Rome conquered Greece at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, up until the Emperor Theodosius suppressed them in 393 AD as part of his strategy to Christianise the empire. Naked men wrestling clearly did not accord with the self-denying ordinances of the Roman church.

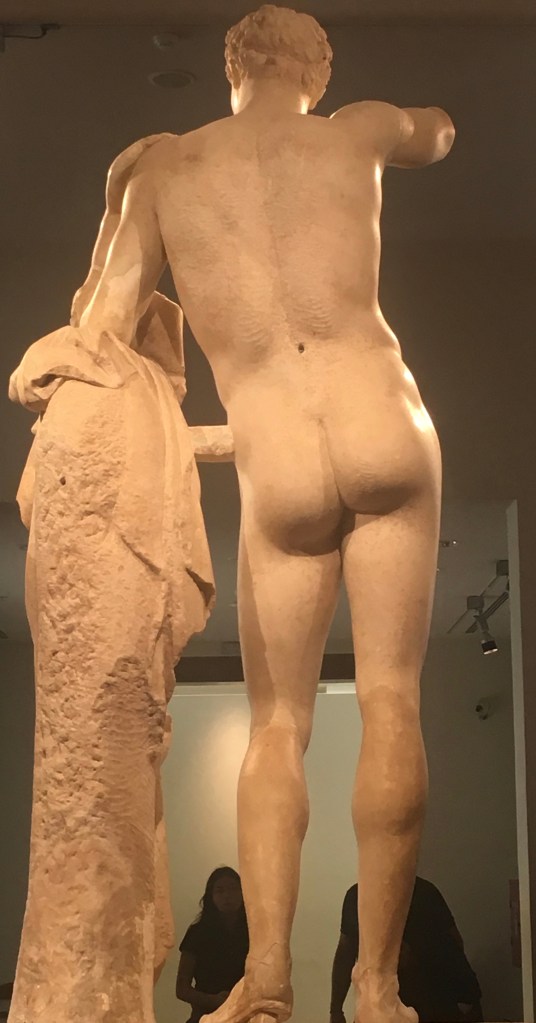

Until their economic troubles in the early part of this century, Greece had taken a cavalier approach to the abundant remnants of antiquity it is blessed with. But their crippling debt burden has made them revisit that cultural wealth with great success. Despite its global appeal, Olympia is not the most magnificent site, but does have one of the finer small museums of its kind. Its central hall houses the remains of the pediments of the Temple of Zeus, the crowning glory of the original Olympia, with the statue of Zeus it contained having been one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. That does not survive, but the last surviving statue by the legendary sculptor Praxiteles – his Hermes of c. 340 BC – does. You can see why the Greek taste for the beauty of the male form did not play so well in the Vatican.

Similarly, the faceless Nike is a robust iteration of the female form which contrasts with the more subservient Marian images favoured by the Roman church. Sculpted by Paionios of Mende in Chalkidiki, Macedonia, in about 420 BC, Nike is the goddess of strength, speed and victory – and would have had wings as well as a face. Originally situated on the south-east corner of the temple of Zeus, with her foot on the eagle emblem of Zeus denoting victory, the Greek inscription translates as: “dedicated by the Messenians and Naupaktians as a tithe of the spoils of their enemies”.

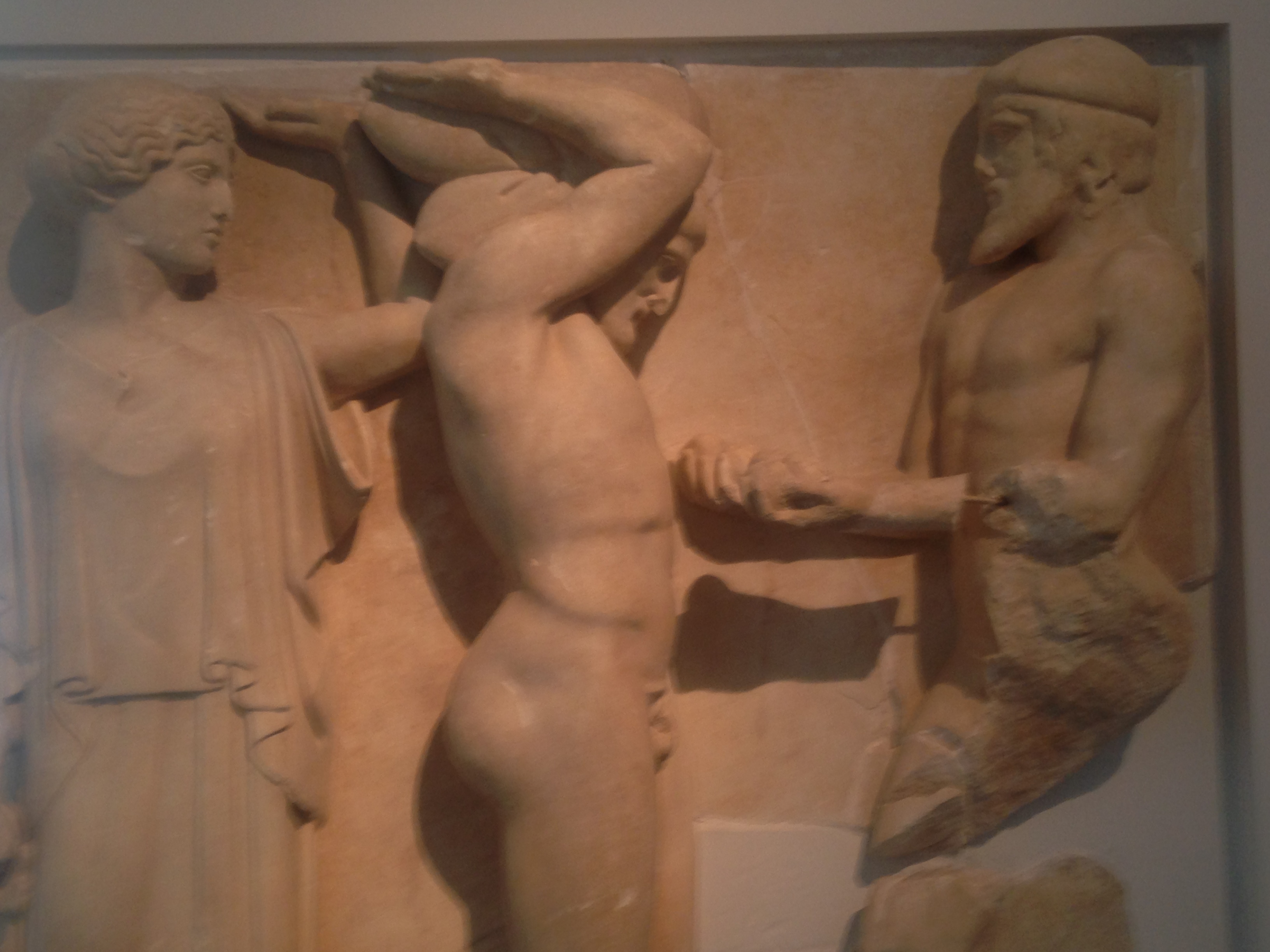

Equally martial is the scene depicted in the remains of the Western pediment of the temple, the battle between Centaurs and Lapiths over the abduction of the Lapith women. Apollo presides over all in the centre, flanked by the heroes Theseus and Peirithoos. Contrastingly, the Eastern pediment opposite depicts the calm before the chariot race between Oinomaos and Pelops, the two champions and their wives flanking Zeus.

Unlike the Romans, the Greeks did not have a large empire spanning the entire known world, but their self-confident pursuit of truth and beauty had a lasting effect not just on that Roman empire’s culture but successive European cultures through the Renaissance to the present day. As Ernst Gombrich, explaining this to the child readers of his Little History of the World, writes:

Whereas the great empires of the East bound themselves so tightly to the traditions of their ancestors they could scarcely move, the Greeks – and the Athenians in particular – did the opposite. Almost every year they came up with something new. Everything was always changing….Always trying out new ideas, never satisfied, never at rest.

Consistent with this tradition, the International Olympics Committee reviews sports that are to be included in upcoming Games, taking the surprising decision in February 2013 to drop wrestling, an event which had been in since the very first games (along with running, boxing and throwing). In September that year they reversed this unpopular decision, and this year’s games was also to have included five new events: baseball/softball, karate, sport climbing, surfing, and skateboarding. This is the antithesis of the spirit animating Brexit, that depressing desire to turn the clock back, resisting foreign intrusion and the imposition of new rules and practices. Most UK developments in environment and work practices in the last 40 years were enforced upon a reluctant Parliament by EU legislation. The draft legislation to replace these advances replaces statutory instruments with voluntary, self-policing compliance, and we all know how assiduous corporations are in putting public interests before profits.

Were we to be able to turn the clock back, it might be preferable to hark back to Athens in the sixth century BC and the original understanding of democracy, where it was an obligation to participate in the demos, and the term idios described the fool who didn’t play their part. The corona virus has revealed some great good in society, where over half a million have volunteered to help the NHS. However, a libertarian government loathe to enforce social isolation at cost to the economy, was forced to because of idiots who flagrantly flaunted the advice to keep their distance. Now there is concern in the Conservative party that – already having had to abandon a policy of fiscal tightness – the long-term fallout of having to impose draconian measures will be held against them at the next election. There is talk of a coalition government, as in 1940-5, sharing the responsibility and thus the blame for whatever happens.

Keir Starmer will have a tough decision to make if so offered, because it will wed him to policies already taken, many of them scandalously late and inadequate, as the editor of the Lancet, Richard Horton keeps calmly stating. Several weeks were wasted before essential medical supplies were sought and restrictions put in place; we have yet to see the full impact of that. The government relies upon the good Blighty spirit which brought people out to cheer the NHS last night to support them come what may, but true democracy is more than a rubber stamp exercise. What prompted Cleisthenes to formulate demokratia (literally power of the people) in 507 BC was the appalling record of tyranny which preceded it. The decade of austerity economics which has now been ditched hardly compares, but there is at least hope that the callous commercial imperatives of the last ten years will be harder to reassert following this period. The targets of the Cummings project – the NHS, the BBC and the civil service – have been the stars of the present – and we all need to ensure that this public realm remains valued in whatever survives the plague. When the Olympics finally take place next year, the Olympic truce needs to reflect a reconsideration of the limits of transnational corporatism.